According to the United States Historical Census Data Base (USHCDB), the ethnic populations in the British American Colonies of 1700, 1755, and 1775 were:

According to the United States Historical Census Data Base (USHCDB), the ethnic populations in the British American Colonies of 1700, 1755, and 1775 were:

{| class=”sort wikitable sortable” style=”font-size: 90%”

{| class=”sort wikitable sortable” style=”font-size: 90%”

! colspan=”6″ |Ethnic composition in the British American Colonies of 1700, 1755, 1775 <ref>McDonald, Forrest, and Ellen Shapiro McDonald. “The ethnic origins of the American people, 1790.” ”William and Mary Quarterly” (1980): 181-199. </ref>

! colspan=”6″ |Ethnic composition in the British American Colonies of 1700, 1755, 1775 <ref name=”Boyer et. al p. 99″>{{Cite book |last1=Boyer |first1=Paul S. |title=The Enduring Vision: A History of the American People |last2=Clark |first2=Clifford E. |last3=Halttunen |first3=Karen |last4=Kett |first4=Joseph F. |last5=Salisbury |first5=Neal |last6=Sitkoff |first6=Harvard |last7=Woloch |first7=Nancy |publisher=Cengage Learning |year=2013 |isbn=978-1133944522 |edition=8th |page=99}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Scots to Colonial North Carolina Before 1775 |url=http://www.dalhousielodge.org/Thesis/scotstonc.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120219045151/http://www.dalhousielodge.org/Thesis/scotstonc.htm |archive-date=February 19, 2012 |access-date=March 17, 2015 |website=Dalhousielodge.org}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=U.S. Federal Census: United States Federal Census : US Federal Census |url=http://www.1930census.com/united_states_federal_census.php |access-date=March 17, 2015 |website=1930census.com}}</ref>

|-

|-

! style=”background:#efefef” |1700

! style=”background:#efefef” |1700

Americans who are descended from the original settlers of the Thirteen Colonies

Ethnic group

| United States and Canada[1] | |

| American English, Pennsylvania German, historical minority Jersey Dutch, Swedish, Finnish, and French. | |

| Christianity (primarily Protestantism, with some Catholicism especially in Maryland) and minority Judaism | |

| British, English, Irish, Welsh, Scots, Ulster-Scots, Old Stock Canadians, Pennsylvania German, New Netherlander, Afrikaners, Huguenots, Anglo-Celtic Australians, European New Zealanders, Anglo-Indians, British diaspora in Africa |

The Old Stock (also called Pioneer Stock or Colonial Stock) is a colloquial name for Americans who are descended from the original settlers of the Thirteen Colonies, especially ones who have inherited last names from that era (“Old Stock families”). Historically, Old Stock Americans have been mainly White Protestants from Northern Europe whose ancestors emigrated to British America in the 17th and 18th centuries.[2][3][4][5]

Settlement in the colonies

The U.S. Census Bureau estimates the population of the Thirteen colonies in July 1776 was 2.56 million.[6] About 90% of the white population was British: English (83.5%), Scottish (6.7%) and Irish (1.6%).[7] In addition there were Germans (5.6%) Dutch (2.0%), French (0.5%) and others down to Hebrew (less than 0.1%).[8]

Early European settlers

Populations of French Huguenots, Dutch, Swedes, and Germans arrived before 1776, some as fellow royal subjects, other populations as legacies of earlier colonies such as New Netherland, which became the Middle Colonies of British America, and the Dutch colonial capital of New Amsterdam retained a distinct commercial cosmopolitan character as New York which became America’s largest city. Ethnic Finns made up the majority of settlers of New Sweden colony which passed to Dutch and English rule. While small in number, Forest Finns left an outsized legacy, among European Americans uniquely accustomed to a pioneer life taming wilderness on frontiers of the Swedish Empire, bringing slash-and-burn agriculture and resourceful timber usage to the New World in the 17th century. From Tavastia, Savo and Karelia, Finnish log cabin architecture arrived early in colonial America, like the 1638 Nothnagle Cabin–adopted by later pioneer settlers like the Scotch-Irish to become symbols of American frontier culture advancing westward across North America.[9] As the Scotch-Irish first resettled Ulster from the violent Scottish borderlands before departing for America, Forest Finns lived on the rough frontier borderlands of eastern Finland until the Swedish king invited them to resettle and clear wooded central Sweden, before remigrating to America.[10][11] In 1776, a descendent of Finnish New Sweden settlers, John Morton, joined Benjamin Franklin and James Wilson to cast the deciding vote of the Pennsylvania delegation in support of independence and became a signer of the Declaration of Independence two days later.[12]

British settlers in New England

While the majority of colonists were from Great Britain, these were not monolithic in ethnic, political, social, and cultural origins, but rather transplanted different Old World folkways to the New World. The two most significant colonies had been settled by opposing factions in the English Civil War and the wider Wars of the Three Kingdoms. The founders of Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay Colony in the North were mostly Puritans from East Anglia, who had been influenced by egalitarian Roundhead republican ideals of Oliver Cromwell’s Commonwealth of England and the Protectorate; in New England they concentrated in towns where decisions were made by direct democracy, prizing communal conformity, social equality, and Puritan work ethic. Partially owing to the insularity of Puritan communities, colonial New England was far more homogeneously “English” than other regions, in contrast to the historically tolerant Dutch colonial parts of the Northeast, and more diverse colonies of the Mid-Atlantic and the South which from an early stage had strong elements of German and Scottish stock, from varying religious traditions.[13][14][15][16]

British settlers in the Old South

Conversely, in Chesapeake Colonies to the south, the Colony of Virginia had been settled by their Cavalier royalist rivals—many younger sons of English gentry who fled Southern England when Cromwell took power, accompanied by indentured servants. Sir William Berkeley, colonial governor of Virginia, loyal to King Charles I, banished Puritans while offering refuge to the Virginia Cavaliers—many of whom became First Families of Virginia. For his colony’s fidelity to the Crown, Charles II awarded Virginia its nickname “Old Dominion”.[17] In contrast to egalitarian and collectivist New England Colonies to the north, settlers of the Southern Colonies in Virginia, Maryland, Carolina, and Georgia recreated a hierarchical social order governed by an aristocratic American gentry which would dominate the antebellum Old South for generations. Sons of British nobility established American plantations where the planter class employed indentured servants to farm cash crops; later replaced by African slaves, especially in Deep South states where a feudal West Indies-style slave plantation economy developed. Freed English American indentured servants, along with Scottish Americans, Scotch-Irish Americans, Palatines and other German Americans arrived as hearty pioneers, taming harsh frontier wilderness to settle their own homesteads amid streams and hilly terrain, becoming old stock of the mountainous backcountry. To contrast against Yankee “Anglo-Saxon” democratic radicalism of New England, at times even English Americans in Dixie (especially in decades leading up to the American Civil War) would not only identify with chivalrous Cavaliers, but even assert a distinct aristocratic racial heritage as knightly heirs to the Normans who conquered and civilized ‘barbaric’ and unruly Anglo-Saxons of medieval England.[14][15][18][19][16]

White settlers arriving in the formerly Mexican holdings of the Southwest were labelled as “Anglos” regardless of their ethnicity.[20]

19th to mid-20th century

Until the second half of the 20th century, the Old Stock dominated American culture and Republican party politics.[21][22] Of the 15 leading American cities, 7 elected a Catholic as mayor before the Civil War, and 13 had done so by 1893. The last two were Edward Dempsey in Cincinnati in 1906, and James Tate in Philadelphia in 1962.[23][24]

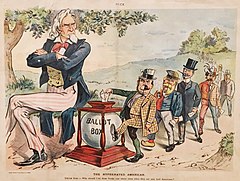

Starting in the 1840s, millions of German and Irish Catholics immigrated to fill new jobs in the rapidly industrializing United States. The Know Nothing movement emerged with an anti-Catholic platform in the North. It had brief success in the mid 1850s, then collapsed. Its presidential candidate, former president Millard Fillmore, took 22% of the total national vote in the 1856 United States presidential election but he was not a party member and he disavowed its anti-Catholic tone.[25]

Sub-groups

Anglo-Americans

The largest old stock ethnic group are the Anglo-Americans, or the English-speaking descendants of the original settlers of the Thirteen Colonies.[26] Despite their name, Anglo-Americans are not entirely of English descent, as many of the original colonists were also German, French, Scandinavian, Dutch, Welsh, Irish, and other European ethnicities.[27][28][29]

According to the United States Historical Census Data Base (USHCDB), the ethnic populations in the British American Colonies of 1700, 1755, and 1775 were:

| Ethnic composition in the British American Colonies of 1700, 1755, 1775 [30] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1700 | Percent | 1755 | Percent | 1775 | Percent |

| English and Welsh | 80.0% | English and Welsh | 52.0% | English | 48.7% |

| African | 11.0% | African | 20.0% | African | 20.0% |

| Dutch | 4.0% | German | 7.0% | Scots-Irish | 7.8% |

| Scottish | 3.0% | Scots-Irish | 7.0% | German | 6.9% |

| Other European | 2.0% | Irish | 5.0% | Scottish | 6.6% |

| Scottish | 4.0% | Dutch | 2.7% | ||

| Dutch | 3.0% | French | 1.4% | ||

| Other European | 2.0% | Swedish | 0.6% | ||

| Other | 5.3% | ||||

| Colonies | 100% | Colonies | 100% | Thirteen Colonies | 100% |

Modern day

|

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (September 2024)

|

See also

References

- ^ Wilson, Bruce G. “Loyalists in Canada”. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- ^ Hirschman, C. (2005). “Immigration and the American century”. Demography. 42 (4): 595–620. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.533.8964. doi:10.1353/dem.2005.0031. PMID 16463913. S2CID 46298096.

- ^ Khan, Razib. “Don’t count old stock Anglo-America out”. Discover Magazine. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ American Baptist Historical Society (1976). Foundations. American Baptist Historical Society. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- ^ Qualey, Carlton (January 31, 2020). “Ethnicity and History”. MSL Academic Endeavors. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- ^ Derick C. Moore, “Looking Back 250 Years: The 1773 Boston Tea Party” (U.S. Bureau of the Census, December 14, 2023) online. It provides ethnic detail for each state in 1790.

- ^ For all those from the British Isles see David Hackett Fischer, Albion’s seed: Four British folkways in America (Oxford UP, 1989).

- ^ For all the ethnic groups see Stephan Thernstrom ed., Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups (1980).

- ^ Purvis, Thomas L. (1999). Balkin, Richard (ed.). Colonial America to 1763 (Almanacs of American Life). New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0816025275. OCLC 39368430.

- ^ Jordan, Terry G.; Kaups, Matti E. (1989). The American Backwoods Frontier: An Ethical and Ecological Interpretation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801836862. OCLC 17804299.

- ^ Wedin, Maud (October 2012). “Highlights of Research in Scandinavia on Forest Finns” (PDF). American-Swedish Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 9, 2017.

- ^ Lossing, B.J. (1857). Biographical Sketches of the Signers of the American Declaration of Independence. New York: Derby & Jackson. p. 112.

- ^ Lind, Michael (January 20, 2001). “America’s tribes – Prospect Magazine”. Prospect Magazine. London: Prospect Publishing Ltd. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ a b Fischer, David Hackett (1989). Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195069051. OCLC 727645641.

- ^ a b Woodard, Colin (2011). American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0670022960. OCLC 810122408.

- ^ a b Watson, Ritchie Devon (2008). Normans and Saxons: Southern Race Mythology and the Intellectual History of the American Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0807133125. OCLC 167763992.

- ^ Salmon, Emily J.; Campbell, Edward D.C., eds. (1994). The Hornbook of Virginia History: A Ready-Reference Guide to the Old Dominion’s People, Places, and Past (4th ed.). Richmond: The Library of Virginia. ISBN 978-0884901778. OCLC 30892983.

- ^ McKee, Jesse O. (August 21, 2017). Ethnicity in Contemporary America: A Geographical Appraisal. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742500341. Retrieved August 21, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Nelson, Eric (2014). The Royalist Revolution: Monarchy and the American Founding. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674735347. OCLC 880122463.

- ^ “The latest to arrive were the English-speaking Americans-called “Anglos” in New Mexico–who began moving in from the east a century ago.” Neville V. Scarfe, “Testing Geographical Interest by a Visual Method.” Journal of Geography 54.8 (1955): 377-387.

- ^ Oyangen, K. Immigrant Identities in the Rural Midwest, 1830–1925. Iowa State University. ISBN 9780549147114. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- ^ Lichtman, Alan J. (2000). Prejudice and the Old Politics: The Presidential Election of 1928. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739101261. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- ^ Melvin G. Holli and Peter D’A. Jones, eds. Biographical Dictionary of American Mayors 1820-1980, (1981) pp.xi, 406–413, 425—426.

- ^ Jenny DeHuff, “Pop quiz: Who was the city’s first Catholic mayor?” PhillyVoice (Dec. 1, 2016) online

- ^ Ray Allen Billington, The Protestant Crusade: 1800-1860: a study of the origins of American nativism (1938) pp. 407–436. online

- ^ The standard history is Marcus Lee Hansen, The Atlantic migration, 1607-1860: A history of the continuing settlement of the United States (Harvard University Press, 1940) pp 25-52.

- ^ UTSA, Institute of Texan Cultures. “Texans One and All – The Anglo-American Texans” (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Kaufmann, E. P. (1999). “American Exceptionalism Reconsidered: Anglo-Saxon Ethnogenesis in the “Universal” Nation, 1776–1850″ (PDF). Journal of American Studies. 33 (3): 437–57. doi:10.1017/S0021875899006180. JSTOR 27556685. S2CID 145140497.

In the case of the United States, the national ethnic group was Anglo-American Protestant (“American”). This was the first European group to “imagine” the territory of the United States as its homeland and trace its genealogy back to New World colonists who rebelled against their mother country. In its mind, the American nation-state, its land, its history, its mission and its Anglo-American people were woven into one great tapestry of the imagination. This social construction considered the United States to be founded by the “Americans”, who thereby had title to the land and the mandate to mould the nation (and any immigrants who might enter it) in their own Anglo-Saxon, Protestant self-image.

- ^ Reginald Horsman (2009). Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism. Harvard University Press. pp. 302–304. ISBN 978-0-674-03877-6.

- ^ McDonald, Forrest, and Ellen Shapiro McDonald. “The ethnic origins of the American people, 1790.” William and Mary Quarterly (1980): 181-199.